Beneath the veil of our solar system’s familiar planets lies a world of paradoxes—Uranus. This distant, blue-green orb, often overshadowed by its gas giant siblings, Jupiter and Saturn, is a realm of extremes: a planet that spins on its side, boasts seasons longer than human lifetimes, and harbors secrets about the formation of our cosmic neighborhood. As the first planet discovered with a telescope, Uranus challenges our understanding of planetary science while offering tantalizing clues about the early solar system. Let’s embark on a journey to unravel the mysteries of this enigmatic ice giant.

A Serendipitous Discovery and Mythological Roots

The Accidental Astronomer

Uranus’s story begins not in ancient times but in the 18th century. On March 13, 1781, British astronomer William Herschel spotted a faint, non-twinkling object in the constellation Gemini. Initially mistaking it for a comet, Herschel soon realized he’d found something far more significant—the first planet identified in recorded history. This discovery doubled the known boundaries of the solar system and cemented Herschel’s legacy.

Naming a New World

The naming of this new planet sparked international debate. Herschel proposed “Georgium Sidus” (George’s Star) to honor King George III, but the suggestion faced resistance outside Britain. German astronomer Johann Bode advocated for a mythological name consistent with other planets. In 1850, the seventh planet was officially named Uranus, the Greek god of the sky and father of Saturn (Cronus). This choice preserved the celestial family tree while breaking tradition—Uranus was a primordial deity rather than an Olympian.

Early Observations and Linguing Questions

Early telescopic studies revealed Uranus’s faint rings and moons, but its great distance (1.8 billion miles from Earth) obscured details. For centuries, astronomers could only speculate about its composition, weather, and peculiar rotation. These questions would remain unanswered until the space age.

Anatomy of an Ice Giant: Structure and Peculiarities

A Layered World of Ices and Gases

Uranus belongs to the “ice giant” subclass, distinct from gas giants like Jupiter. Its interior is a layered cocktail of hydrogen, helium, and ices—not frozen water, but a hot, dense fluid of water, ammonia, and methane under extreme pressure. Scientists theorize three main layers:

- A Rocky Core: A small, silicate-iron core roughly half Earth’s mass.

- Mantle of “Icy” Slush: A vast, supercritical fluid mantle comprising most of the planet’s bulk.

- Gaseous Atmosphere: Primarily hydrogen (83%) and helium (15%), with traces of methane that give the planet its cyan hue.

The Tilt That Defies Convention

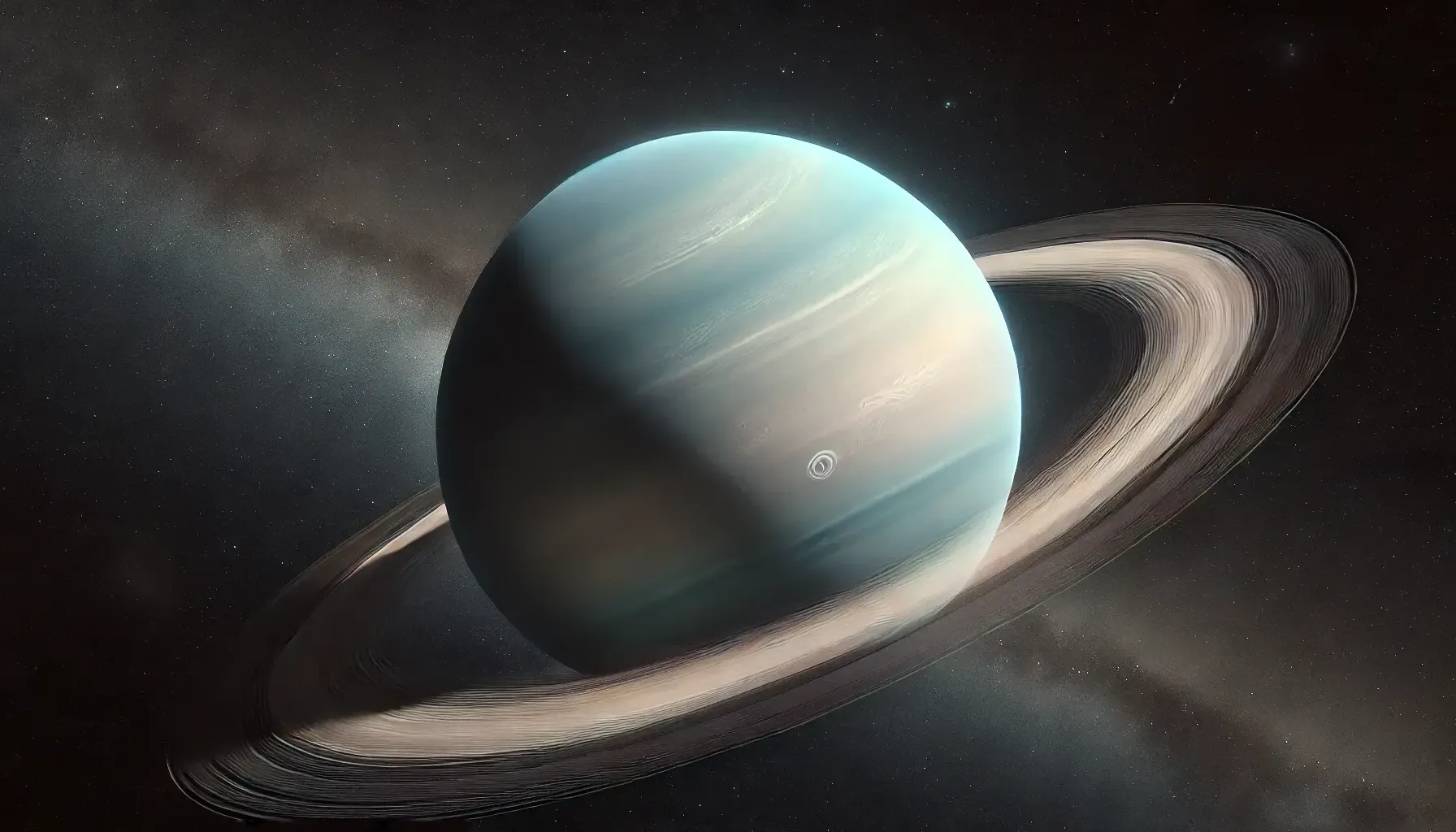

Uranus’s most striking feature is its axial tilt: 98 degrees. While Earth leans at 23.5 degrees, this ice giant essentially orbits the Sun on its side. A cataclysmic collision with an Earth-sized protoplanet likely caused this tilt, reshaping its rotation and possibly triggering internal heat loss. Unlike other giants, Uranus radiates little excess heat, making it the solar system’s coldest planet (-371°F).

Atmospheric Drama: Quiet Yet Complex

Despite its placid appearance, Uranus’s atmosphere churns with dynamic processes. High-altitude methane clouds streak across its upper layers, driven by winds exceeding 560 mph. In 2014, the Keck Observatory detected massive storms—a surprise for a planet once deemed meteorologically inert. Seasonal shifts, caused by its extreme tilt, may explain these outbursts, though the exact mechanisms remain unclear.

A Magnetic Enigma

The ice giant’s magnetic field defies expectations. Offset by 60 degrees from its rotational axis and tilted asymmetrically, the field likely originates from electrically conductive fluids in its icy mantle rather than its core. This “off-kilter” magnetosphere creates a complex interaction with solar wind, leading to irregular auroras and particle dynamics.

Rings, Moons, and Orbital Dynamics

The Subtle Elegance of Uranian Rings

Uranus hosts 13 known rings, narrow and dark compared to Saturn’s icy bands. Composed of charcoal-colored particles likely altered by radiation, they may be remnants of shattered moons. The epsilon ring, the brightest, features shepherd moons Cordelia and Ophelia that confine its structure through gravitational nudges.

Moons of Ice and Mystery

27 moons orbit Uranus, named after Shakespearean and Alexander Pope characters. Five stand out:

- Miranda: A fractured world with 12-mile-high cliffs, suggesting past tectonic upheaval.

- Titania and Oberon: The largest moons, bearing possible subsurface oceans beneath icy crusts.

- Ariel and Umbriel: Geologically active Ariel contrasts with Umbriel’s ancient, cratered face.

These moons hint at cryovolcanism and tidal heating, though Uranus’s weak gravity complicates such theories.

Orbital Oddities and Seasonal Extremes

Uranus’s 84-year orbit creates seasons lasting 21 Earth years. During solstices, one pole basks in perpetual sunlight while the other plunges into darkness. Equinoxes bring fleeting moments of day-night balance, triggering global atmospheric upheavals.

Voyager 2 and the Quest for Knowledge

A Lone Encounter

In 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 became the only spacecraft to visit Uranus. The flyby revealed 10 new moons, two rings, and a bland atmosphere masking hidden storms. Data on its magnetic field and composition reshaped ice giant theories, yet many questions lingered.

The Case for a Return

Decades later, Uranus remains a priority for exploration. Proposed missions like NASA’s Uranus Orbiter and Probe aim to study its atmosphere, interior, and moons. An onboard probe could analyze atmospheric chemistry, while orbiters might map magnetic fields and hunt for subsurface oceans.

Uranus in Context: Ice Giants and Planetary Evolution

Ice Giants vs. Gas Giants

Uranus and Neptune differ fundamentally from Jupiter and Saturn. Their higher proportions of volatile ices (water, methane, ammonia) suggest they formed farther from the Sun, where temperatures allowed these compounds to condense. Their smaller sizes and lack of metallic hydrogen layers further distinguish them.

A Missing Piece in Planetary Formation

Ice giants may represent the most common exoplanet type, yet our solar system has only two. Studying Uranus helps explain their scarcity here and informs models of planetary migration. Some theories posit that Jupiter’s inward motion scattered primordial ice giants, leaving Uranus and Neptune as survivors.

Cultural Legacy and Modern Inspiration

From Mythology to Modernity

Uranus’s mythological roots as the sky god permeate astrology and literature. Though less prominent in pop culture than Mars or Saturn, it appears in sci-fi like Arthur C. Clarke’s 2061: Odyssey Three and serves as a metaphor for the unknown.

A Beacon for Future Exploration

This ice giant symbolizes humanity’s relentless curiosity. As astronomers discover countless Uranus-like exoplanets, understanding our local specimen becomes ever more critical. Its storms, tilted magnetosphere, and icy moons challenge assumptions, reminding us that the solar system still holds untold stories.

Expanding the Horizon: The Future of Uranian Exploration and Cosmic Significance

The Urgency of Ice Giant Missions

Uranus has languished in scientific limbo since Voyager 2’s brief visit, but the tide is turning. In the 2023 Planetary Science Decadal Survey, the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine ranked a Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP) as the highest-priority flagship mission for NASA in the next decade. This ambitious project, potentially launching in the early 2030s, would deploy an atmospheric probe to dive into the planet’s haze-shrouded skies and an orbiter to study its moons, rings, and magnetic field over multiple years.

Why the sudden push? Uranus holds answers to questions central to planetary science:

- Planetary Migration: Did ice giants form closer to the Sun before migrating outward, as the “Nice Model” of solar system evolution suggests?

- Atmospheric Chemistry: How do methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other compounds behave under extreme pressures?

- Exoplanet Analog: Over 30% of known exoplanets are Neptune-sized; understanding Uranus helps decode these distant worlds.

Technological Hurdles and Innovations

Reaching Uranus requires overcoming daunting challenges. At 1.8 billion miles from Earth, sunlight there is 400 times dimmer than on our planet, necessitating nuclear power sources like advanced radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). Communication delays of up to 3 hours one-way demand autonomous spacecraft systems capable of real-time decision-making.

Proposed solutions include:

- Solar Electric Propulsion: For efficient, sustained thrust during the 12-15-year cruise phase.

- AI-Driven Instruments: To prioritize data collection during fleeting flybys of moons.

- Cryovolcanic Samplers: Hypothetical tools to analyze plumes from moons like Miranda.

The Search for Life in Frozen Shadows

While Uranus itself is inhospitable, its moons—particularly Titania and Oberon—raise astrobiological intrigue. These worlds may harbor subsurface oceans kept liquid by tidal heating or residual radiogenic warmth. On Earth, life thrives in similarly extreme environments, such as Antarctic subglacial lakes. If Uranian moons have:

- Chemical Energy Sources (e.g., hydrothermal vents),

- Organic Molecules, and

- Stable Liquid Water,

they could host microbial ecosystems.

A 2022 study in The Planetary Science Journal posited that Miranda’s fractured terrain might indicate recent geologic activity, a potential energy source for life. While speculative, these ideas underscore why Uranus’s moons are compelling targets.

Uranus as a Cosmic Mirror: Reflecting Solar System History

The ice giant’s composition acts as a time capsule. Unlike Jupiter and Saturn, which accreted massive amounts of gas from the primordial solar nebula, Uranus and Neptune likely formed later, from slower-growing ice-rich planetesimals. Their chemical makeup—particularly the ratio of hydrogen to heavier elements—preserves clues about the density and temperature of the early solar system’s outer reaches.

Recent isotopic analyses of meteorites suggest that Uranus might contain material from the “frost line,” the boundary beyond which volatile compounds like water and ammonia could condense. Studying its atmosphere could reveal how these materials were distributed during the solar system’s chaotic infancy.

Climate Mysteries: Unlocking Atmospheric Superrotation

One of Uranus’s enduring enigmas is its atmospheric superrotation—a phenomenon where winds blow faster than the planet rotates. While common on Venus, this behavior is poorly understood in ice giants. On Uranus, equatorial winds lag behind the planet’s rotation, while mid-latitude jets race eastward at 560 mph.

A 2023 University of Leicester study proposed that methane condensation in the upper atmosphere releases latent heat, driving these wind patterns. Confirming this would refine climate models for gas giants and exoplanets alike.

Collaborative Global Efforts

The European Space Agency (ESA) is considering complementary missions, such as a Uranus Pathfinder orbiter or a focused ice giant probe. Meanwhile, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has already begun studying Uranus’s atmosphere in infrared, identifying previously unseen storm systems and refining thermal profiles.

International collaboration will be key. For example, NASA’s UOP could partner with JAXA (Japan) for probe technology or with ESA for communications infrastructure. Such alliances distribute costs—estimated at $4–6 billion for a flagship mission—while pooling expertise.

Ethical and Philosophical Dimensions

Exploring Uranus isn’t just a technical feat; it’s a philosophical journey. The planet’s vast distance from Earth—a three-billion-mile round trip for signals—forces humility. Each byte of data returned is a testament to human ingenuity and patience, a counterbalance to our era of instant gratification.

Moreover, Uranus challenges anthropocentrism. Its sideways spin, lack of a solid surface, and extreme seasons remind us that “habitability” is a human-defined concept. The universe teems with worlds that defy imagination, each governed by its own physics.

Education and Public Engagement

Uranus’s quirky features—its name, tilt, and icy blue glow—make it a potent tool for science communication. Initiatives like NASA’s “Solar System Ambassadors” program leverage its peculiarities to teach orbital mechanics, planetary formation, and climate science. Artists and writers, too, find inspiration in its mysteries; recent works like The Ice Giant Chronicles (a sci-fi anthology) and immersive planetarium shows highlight its role in popular culture.

The Road Ahead: A New Golden Age of Exploration

If the 20th century was the era of lunar landings and Martian rovers, the 21st may belong to the ice giants. Uranus and Neptune represent the final frontiers of our solar system, the last unvisited planets. With advances in propulsion (e.g., nuclear thermal rockets) and miniaturized sensors, missions once deemed impossible are now within reach.

A Uranian orbiter could arrive by 2045, coinciding with the planet’s northern vernal equinox—a rare chance to observe seasonal changes in real time. Imagine: hurricanes erupting as sunlight first strikes darkened poles, methane storms crackling through silent skies, and robotic eyes capturing it all.

Final Reflections: Beyond the Blue-Green Marble

Uranus, often dismissed as a featureless “iceball,” is anything but. It is a dynamic laboratory for physics, a storyteller of cosmic history, and a beacon for interstellar ambition. To study it is to confront the limits of human knowledge and push beyond them.

As we stand on the cusp of a new exploratory era, let us channel the curiosity of William Herschel, who gazed into the unknown and saw not just a point of light, but a world waiting to be understood. In the words of planetary scientist Heidi Hammel, “Uranus is the puzzle box of the solar system. Every layer we peel back reveals more questions—and that’s what makes it beautiful.”

The ice giant’s greatest lesson may be this: In the vastness of space, even the oddities have purpose. Uranus, with its sideways dance and silent storms, invites us to keep looking up, to keep wondering, and to keep sailing—literally and metaphorically—into the unknown.